Medical aid in dying: States debate right-to-die laws

ALBANY, N.Y. - On a spring morning in Albany, New York, a group of people gathered at the Capitol to share poignant stories of grief and suffering. They lit candles and read aloud the names of 22 people who have lost their lives while waiting for their cause to be heard: The right to die "with dignity."

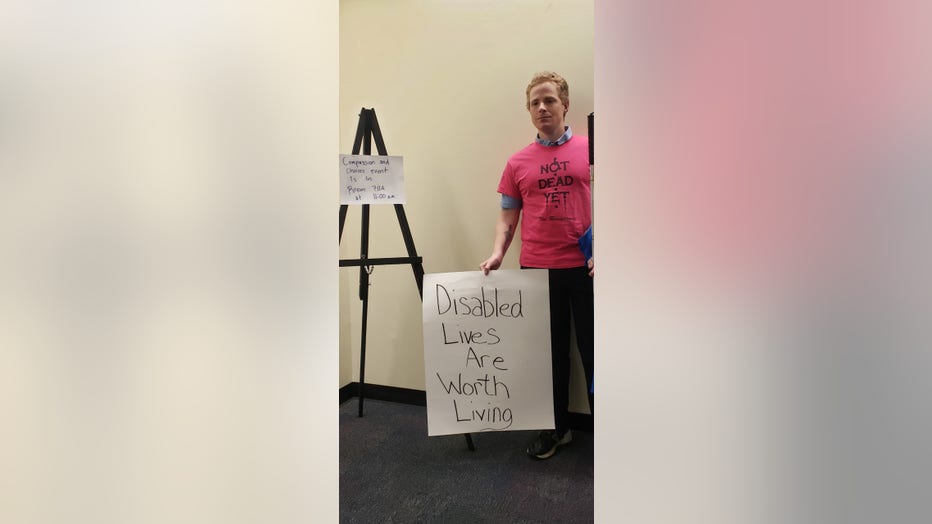

Outside and in the same room, a smaller group of advocates emerged. They held signs and stood strong with their own message for lawmakers to hear: "Not dead yet."

New York is one of several states where lawmakers have introduced bills to legalize medical aid in dying, which allows doctors to prescribe lethal medication to terminal, mentally competent patients with a prognosis of six months or less to live — if they ask for it. It’s currently legal in 10 states and Washington, D.C.

Proponents say these laws allow people to end their lives on their own terms, without the drug-resistant physical and emotional suffering that often comes with terminal illness. Opponents argue it’s a policy with little to no oversight that can lead to coercion from caregivers — and even outright abuse of people who are terminally ill.

‘Your death, your choice’: The case for medical aid in dying

Susan Rahn (photo courtesy Compassion and Choices)

Susan Rahn of Rochester, New York, was diagnosed with stage 4 metastatic breast cancer in 2013. Doctors told her there was no cure, and the median lifespan for her disease was about 18 months, she said.

"At the time, my son was 14 years old," Rahn said in an interview with FOX Television Stations. "I was really terrified of not just leaving my son, but having him have memories of me dying. I didn’t want to do that."

About a year later, Rahn learned about medical aid in dying through Brittany Maynard, who was 29 years old when she was diagnosed with brain cancer and told she had six months to live.

After months of research, Maynard concluded there was no treatment to save her life — and because of the aggressiveness of the tumor, it would likely be a brutal death.

"Brittany said, ‘I will not die like that,’" Maynard’s husband, Dan Diaz, told FOX Television Stations.

Maynard and Diaz packed up their belongings and moved from California to Oregon, one of four states in the U.S. where medical aid in dying was legal at the time. A few months later, Maynard shared her story on YouTube. More than 12 million views later, she unknowingly became the face of the death-with-dignity movement.

Brittany Maynard and Dan Diaz (Photo courtesy Dan Diaz and TheBrittanyFund.org)

"That was not her intent," Diaz offered. "She wanted legislators to hear her message…so that nobody would ever have to do what we did and leave your home with less than six months left to live."

Maynard ended her own life on Nov. 1, 2014. She died in her husband’s arms.

Rahn hasn’t had to face that reality yet. She has defied doctors’ prognoses with specialized treatment, but "at some point, my treatment is going to fail, and it will continue to go through my body until there are no treatments left for me."

"I’ve been really, really lucky," Rahn continued. "This is really unusual ... I kind of live my life in six month increments."

According to data compiled by Compassion and Choices, the leading advocacy group for medical aid in dying, in the 20-plus years since it has been authorized anywhere in the U.S., 5,171 people have taken a prescription to end their suffering. In Oregon, the first state in the nation to legalize it, 3,280 people have received lethal prescriptions since 1997. Of those, 2,159 have taken them as of December 2021.

Proponents argue a third of people who obtain the prescription never ingest the pills, and less than 1% of the people who die in each state use the law each year. The majority of terminally ill people who used medical aid-in-dying — more than 86% according to Compassion and Choices — received hospice services at the time of their deaths.

Diaz said in most cases, hospice and palliative care can keep dying patients at least somewhat comfortable. But "that’s not 100%," he said, and "Brittany’s case was one of them."

"We only get to do this once," Diaz said. "We live this crazy life, this rollercoaster, and we die one time. Do I want my death to be filled with suffering and pain that not even morphine can relieve?"

‘More harm than good’: The case against physician-assisted suicide

Aaron Baier, director of administration for the Independent Living Center of the Hudson Valley (photo credit: Julie Farrar)

If someone is diagnosed with cancer, but declines chemotherapy, should a doctor help them die? Should people suffering from mental illness like anorexia nervosa be able to end their lives with a prescription?

It’s questions like these that fuel opposition to physician-assisted dying, or what some opponents call "assisted suicide."

"They grant broad immunities to doctors and others involved," said Diane Coleman, a disability advocate who founded the organization Not Dead Yet in 1996 to oppose physician-assisted suicide. "The only real data is reported by the prescribing doctor; there’s no meaningful oversight."

The American Medical Association has debated the issue in recent years and hasn’t changed its stance: that ultimately, physician-assisted death does more harm than good.

"That six months or less is a prognosis," said Matt Vallière, executive director of the Patients Rights Action Fund, a nonpartisan, secular organization opposed to physician-assisted suicide. "It’s a best guess by physicians, and those physicians will readily admit that it’s not a hard and fast thing. They’re not very good at prognostication."

Matt Vallière speaks with FOX TV Stations

Vallière began lobbying against aid-in-dying laws in 2012, when his home state of Massachusetts put the issue on the ballot for voters to decide. Polls leading up to the vote showed 70% approval, Vallière said, but on election day the measure failed in a 51%-49% vote.

"This makes suicide a medical treatment," he said. "It’s coded by your doctor, your insurance company. Your doctor, your pharmacist and your insurance are now involved. In some cases your insurer will pay for this, while denying you coverage for other things."

The lack of oversight could lead to tired and overworked caregivers giving patients the medication against their will, Vallière said. He said it also allows doctors to skirt requirements without consequence.

"You have to be competent at the time of request, not the time of ingestion. Not a single one of them has a requirement that a third party be present at the time of ingestion to ensure competence and that it’s voluntary," Vallière said.

Coleman, of Not Dead Yet, has a form of muscular dystrophy and has been in a motorized wheelchair since she was 11 years old. She’s had breathing support for the past 20 years and still works fulltime.

Diane Coleman

"People’s reasons for assisted suicide are disability issues — a loss of autonomy, the stress of not being able to do the same things, feeling like a burden of others. Those are the kinds of concerns that we understand very well," Coleman said.

Coleman started her organization in 1996, the same year Dr. Jack Kevorkian was acquitted on criminal charges that he helped two women kill themselves in Michigan. It’s also the same year physician-assisted death was going before the U.S. Supreme Court.

American pathologist Jack Kevorkian seen in a mug shot from November 2005. (Photo by Kypros/Getty Images)

Coleman and other disability advocates warn aid-in-dying laws can lead to unintended, life-or-death consequences that "set up a change, a set of expectations in society and in a health care system that already sees people like me as a bit too expensive."

"We face a lot of difficulty in getting the services we need just to get up in the morning … Whatever we need, it’s a struggle still," she said. "The answer is to provide the supports we need, not to kill us."

Oregon pioneers ‘Death with Dignity’

Oregon was the first state in the nation to allow medical aid in dying after enacting the Death with Dignity act in 1997. In March, it became the first state to eliminate residency requirements for patients seeking end-of-life care. Now, advocates say they’ll use Oregon’s precedent to push other states to allow anyone access to aid-in-dying where it’s legal.

The new policy in Oregon was in response to a lawsuit filed by an Oregon doctor and Compassion and Choices, but the suit addressed a specific grievance — that the doctor wasn’t able to provide aid-in-dying medication to the patients he sees in neighboring Washington state. It won’t have much of an impact on people elsewhere who are seeking end-of-life medication.

Amitai Heller, senior staff attorney for Compassion and Choices, said people from out-of-state who would consider going to Oregon for aid in dying would have "quite a few challenges."

"It’s extremely difficult for people who are dying to get on a plane, find a new attending physician, establish a therapeutic relationship, handle the logistics," Heller said. "It’s extremely useful for people to have this option, but it will only affect a small group of people who are able to travel."

Where medical aid-in-dying is legal

MAP: Trouble viewing the map? Click here to enlarge

Medical aid in dying is currently legal in 10 states and Washington, D.C.:

- Oregon

- Washington

- Montana

- Vermont

- California

- Colorado

- Washington DC

- Hawaii

- New Jersey

- Maine

- New Mexico

Laws have been proposed in the following states, but they have not been passed or enacted:

- Nevada

- Arizona

- Kansas

- North Dakota

- Minnesota

- Iowa

- Indiana

- Kentucky

- Virginia

- Pennsylvania

- New York

- Massachusetts

- Connecticut

- Rhode Island

In New York, where people like Rahn and Coleman are fighting on opposite sides of an emotionally charged issue, the measure has been introduced several times since 2016. This year, New York’s Medical Aid-in-Dying Act never made it out of committee.

This story was reported from Seattle.